How to Communicate in a World of AI

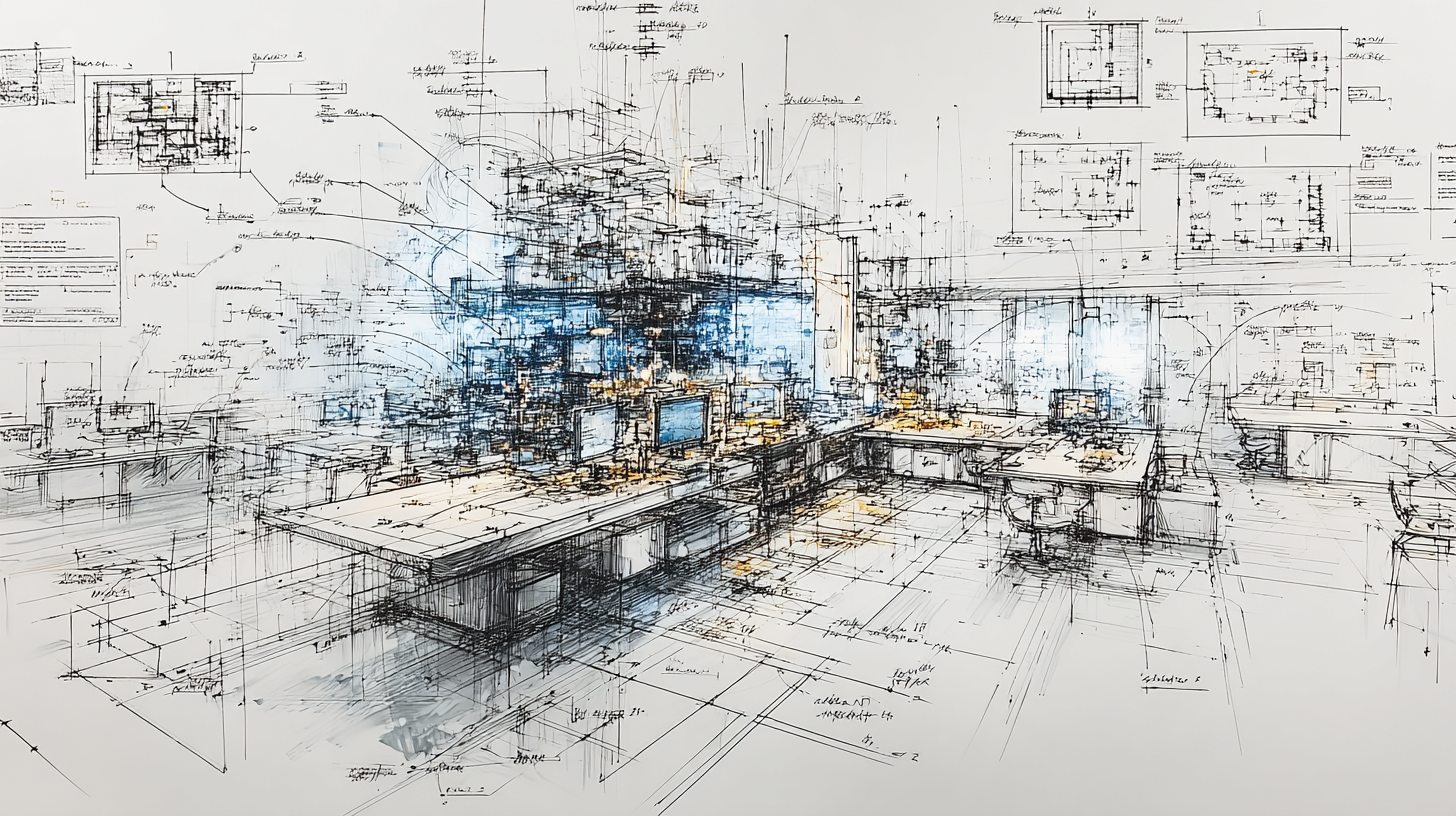

Why “specification thinking” is the new office superpower

Most office work is already a kind of “programming,” just not in the narrow software sense. Any time you ask for a report, propose a change, approve a process, write a policy, or request analysis, you’re translating intent into a repeatable outcome.

AI makes drafting and execution faster. That’s a real advantage—but it also changes what’s scarce. When “doing” gets easier, the bottleneck shifts toward knowing what you want and communicating it precisely.

In many organizations, the durable asset isn’t the one-off output. It’s the structured communication that produced it: the goals, constraints, context, and checks that let a team regenerate quality work across tools, people, and months.

That structured communication is a specification.

This creates a distinction that matters for everyone:

- Writing expresses ideas.

- Coding implements solutions.

- specifications bridge intent and execution: a durable, testable statement of what you mean.

In other words: specifications are becoming a shared language for organizations—a way to align humans and machines on the same intent.

The shift: from Questions to Prompts to Specifications

Many people first learn AI by asking it a bunch of questions. Then when that doesn’t work, they are told to move onto “prompting.” And this feels productive because it often is: you describe what you want, and the system produces output quickly.

But there’s a trap: teams often keep the generated output and discard the prompt. That’s backwards for any work that needs to be repeatable, auditable, or safely delegated.

In software, the compiled executable isn’t the main artifact. The source code is what you version, debate, and regenerate from. Likewise, in AI-enabled knowledge work, the long-lived asset isn’t “the draft you got this time.” It’s the repeatable instruction set that reliably produces good drafts across scenarios.

That repeatable instruction set is a specification and specifications have been around a lot longer than AI. They are:

- Durable (doesn’t vanish after one chat session)

- Shareable (humans can read and review it)

- Version-controlled (you can track changes over time)

- Testable (you can check outputs against it)

- Reusable (it can generate many downstream artifacts)

Prompts vs Specifications vs Evaluation

To make this concrete, it helps to separate three things that often get blended together:

- A prompt is a one-time instruction to get an output.

- A specification is a reusable contract for what “good” means.

- An evaluation is the checklist or rubric that enforces that contract.

Prompting gets you drafts. Specifications & Evaluations get you repeatable quality.

What a “specification” Looks Like

Think of a specification as a contract between intent and execution. It doesn’t need to be fancy. It needs to be clear enough that:

- other humans can align on it, and

- a collaborator (human or AI) can produce work that conforms to it.

A practical office specification usually includes:

1) Purpose & Outcomes

- What are we trying to achieve?

- What changes if this is successful?

2) Audience & Use-Case

- Who will read/use this?

- What decisions will they make from it?

3) Scope & Boundaries

- What’s in / out?

- What assumptions are allowed?

- What risks must be avoided?

4) Inputs & Allowed Sources

- What data or references are authoritative?

- What is explicitly not allowed (e.g., sensitive sources, unverified numbers)?

5) Success Criteria

- What does “good” look like?

- How will we tell it’s correct, complete, and useful?

6) Examples & Edge Cases

- One “good” example and one “bad” example often beats paragraphs of explanation.

This is why specifications are more foundational than “just writing” and more reusable than “just coding”: they capture intent with enough precision to generate many downstream artifacts—emails, decks, policies, analysis, FAQs, training, and yes, software behavior.

Why Specifications Matter More in an AI Era

Outputs are a lossy projection of intent. Even great output doesn’t fully encode:

- why it exists,

- what tradeoffs were made,

- what “correct” means in context, or

- what success looks like for the audience.

You can see this everywhere:

- A dashboard is a lossy projection of what leaders wanted to know and what actions they hoped it would trigger.

- A policy is a lossy projection of the risks it was meant to manage and the values it was meant to encode.

- A process doc is a lossy projection of the outcome the process was created to produce.

AI accelerates producing the projection. It does not automatically preserve the intent behind it. specifications do.

“Executable Specifications”

You can make specifications “executable” by pairing them with tests—ways to check whether the output matches the specification. In software, that’s unit tests. In engineering, it’s verification and validation. In business, it shows up as QA, controls, review checklists, and scoring rubrics.

For office work, “executable” just means:

- you can “run” the specification to produce valuable output, and

- you can evaluate the output against the specification and say pass/fail (or grade it).

Examples:

- If the specification says “must include risks and mitigations,” the check is: are risks specific, prioritized, and mitigations actionable?

- If the specification says “audience is VPs, 2-minute read,” the check is: length, structure, jargon level, and decision clarity.

- If the specification says “avoid flattery; prioritize evidence,” the check is: does the output make grounded claims, and does it avoid unearned praise?

This creates a loop that improves quality over time:

specification → generate → evaluate → revise specification

Example: Specification → Draft → Evaluation → Revised Specification

Here’s an end-to-end example that has a non-AI, non-computer, example that works at an Electric Utility Company. Again this is Illustrative only—you must use your approved safety/wildfire procedures and operating standards.

The specification

- Goal: One-page decision memo: proceed with an urgent repair outage vs defer with interim controls for damaged distribution equipment in a High Fire Risk Area in Southern California.

- Audience: Distribution Ops Director + Safety + Wildfire Mitigation (skimmable in ~2 minutes).

- Context: Field patrol flagged damaged overhead hardware on a WUI circuit. Wind event risk within ~48 hours. Multiple feasible paths; decision must be documented.

-

Constraints (must / must not):

- Must cover 5 risk lenses: public safety, worker safety, wildfire/ignition exposure, reliability/customer impact, regulatory/reputation.

- Must pair each risk with specific controls and an owner (role/team).

- Must separate confirmed facts from assumptions/unknowns (and list what would change the decision).

- Must include no-go / stop-work triggers by referencing internal criteria (no invented thresholds).

- Must avoid absolute language (“safe,” “zero risk,” “guaranteed”).

- Output format: Title + Situation (2 bullets) + Options (2–3) + Risks/Controls (5 lines) + Decision.

- Success criteria: A leader can pick an option without a follow-up meeting; rationale is defensible and auditable.

Examples of “good” vs “bad”

- Good (risk + control + owner): “Worker safety: narrow shoulder + night work increases struck-by exposure → Control: daylight window if feasible; traffic control per standard; dedicated spotter → Owner: Field Safety + Supervisor.”

- Good (facts vs assumptions): “Fact: cracked insulator observed (photo

- pole ID + timestamp). Assumption: wind risk may increase in next 48 hrs; if internal trigger reached, switch to no-go posture and escalate.”

- Bad (vague / non-auditable): “It’s risky out there—everyone should be careful and follow procedures.”

- Bad (overpromising): “If we do the outage tonight there’s no chance of a fire.”

Draft (excerpt only)

Urgent Repair Decision — WUI Circuit Hardware Damage (Draft)

-

Situation (facts): Damage confirmed on overhead hardware (field photo + supervisor assessment). Unknowns: forecast timing/intensity; crew availability; switching complexity.

-

Options:

- A) Outage + repair within 24 hrs (remove known defect sooner; customer impact + rapid mobilization risk)

- B) Defer 72 hrs + interim controls (better staffing/daylight; continued exposure to known defect)

- C) Escalate posture if conditions meet internal criteria (per wildfire/safety standards)

-

Top risks + controls (owner):

- Public safety during outage → customer notifications + critical customer checks (Customer Ops)

- Worker safety (fatigue/traffic) → shift limits + JHA + traffic plan + safety observer (Safety/Supervision)

- Ignition exposure → interim mitigation actions + increased patrol/escalation (Wildfire Mitigation)

- Reliability impact → switching plan + contingency if job runs long (System Ops)

- Regulatory/reputation → document rationale + evidence retention + accurate comms (Regulatory/Comms)

-

Decision needed: Select A/B/C and confirm owners + no-go triggers.

Evaluation checklist (0–2 points for each)

- Facts vs assumptions separated, with “what would change the decision”?

- Five risk lenses covered (not just safety + outage)?

- Each risk has a concrete control and an owner?

- No-go/stop-work triggers included without inventing thresholds?

- Options are comparable (pros/cons) and bounded?

- Reads in ~2 minutes?

Revised specification (v1 upgrades)

Two tweaks make this “enterprise-repeatable”:

- Add Evidence required for key facts (photo/inspecificationtion/work order

- date/time).

- Require Notifications + recordkeeping (who is notified; where the decision record lives; owner).

That’s the point: improve the specification so the next memo is better by default. If you get feedback on the output, don’t just tweak the memo—tweak the specification so the next one is better.

How Specifications Create Trust

When you have a specification, you have a shared reference point for judging outcomes:

- If the specification says “don’t do X,” and the output includes X, you can call it a defect without turning it into a personality debate.

- If the specification says “VP audience, 2-minute read,” and you get a 6-page essay, you can reject it for a clear reason.

In organizations, this matters because teams waste time arguing about whether something is “right” when they never aligned on what “right” meant. A specification becomes a trust anchor: disagreements become resolvable because the criteria are explicit.

This applies everywhere:

- “What counts as a compliant response?”

- “What counts as an acceptable summary?”

- “What tone represents our brand?”

- “What decisions should this document enable?”

- “What does ‘secure enough’ mean for this workflow?”

If you can’t point to the specification, you don’t have alignment—you have opinions. Expert opinions work in the short term, but they don’t scale. Specifications scale. Corporations are built to address problems at scale. If you are not building solutions that scale, you are building fragility. If you are building solutions that only scale with constant expert intervention, you are building high-cost, slow, brittle solutions at scale. Specifications are how you build low-friction, high-trust solutions at scale.

What This Means for Office Workers

The Career Advantage Isn’t “Prompting”

It’s specification-writing: capturing intent, constraints, and success criteria so clearly that:

- a collaborator (human or AI) can produce a strong draft,

- colleagues can review it quickly,

- the result is repeatable and auditable.

Many “AI failures” Start as Specification Failures

A common pattern is:

- “It didn’t do what I wanted.”

Often meaning:

- “I didn’t fully specify what I meant, what I cared about, or how to judge success—and I didn’t verify understanding.”

That’s not always the whole story (as people and models have real limits), but better specifications reduce rework and reduce the blast radius when something goes wrong.

Specifications Let More People Contribute Safely

As AI becomes normal in day-to-day work, plain, shareable specifications let legal, risk, policy, operations, product, and engineering collaborate on the same intent without constant translation.

In the past engineering specifications were written in formal languages that are trapped in printed books and PDFs. In the AI era specifications need to be more fluid, more shareable, and more version-controlled. One lesson IT Engineering has learned is to move away from the static approaches. We now use plain text files that incorporate Markdown(MD) and Markup(XML/JSON/YAML). These formats are machine readable as well as human readable. This allows AI systems to parse, understand, and generate specifications that can be used across the organization.

In enterprise terms: specs are the collaboration layer between business partners and the machines that execute on those agreements.

A Practical Playbook: “Specification First” for Your Next Task

When you’re about to do something important (analysis, comms, policy, plan, requirements), do this:

-

Write 6 bullets before you begin

- Goal

- Audience

- Context

- Constraints (must / must not)

- Output format

- Success criteria

-

Treat that as the real artifact Save it. Version it. Reuse it. Improve it.

-

Add 2 examples

- “A good answer looks like…”

- “A bad answer looks like…”

-

Evaluate output against the specification Don’t just “feel” if it’s good—check it.

-

Refine the specification, not the vibe If the result is wrong, update the specification so the next run is better.

Takeaway

In a world where AI makes drafting and execution faster, clarity becomes the scarce resource—and therefore valuable. specifications are durable clarity. They align humans, guide machines, and build trust because they make success criteria explicit.

So the most “normal office worker” advice is also the most powerful:

Stop thinking: “How do I…” Start thinking: “What do I actually mean — and what proof do we need to demonstrate we got it right?”