Intro

Leaked reports indicate that Microsoft, in partnership with OpenAI, is planning to invest an astounding $100 billion into a new AI data center. This massive amount is more than double the global annual expenditure on data centers. What cutting-edge technologies and innovations might go into this facility, and what special considerations must be tackled when spending such significant sums on AI-centric infrastructure? Keep watching to learn more. This has three parts: “Data Center Gold Rush,” “So You Want to Build a Data Center,” and “The Hardware Secret Sauce.”

Part 1: Data Center Gold Rush

Most software these days relies on servers, and servers live in data centers. Although you’ve probably heard of the cloud as a big provider of data centers, data centers come in many different sizes. On the small end, you might have a small company that has 10 racks. Let’s say a server rack is basically a big vertical closet that you can put servers into. Each rack is divided into 42 units, which is a measurement of space. An average server might take up three units, although you can get much larger servers. For example, you can get six-unit servers and so on. If an average server takes three units of space, you can get maybe 14 servers into a rack. So a 10-rack data center can essentially hold 140 servers. Building something like this might cost between $200,000 and $500,000 USD, somewhere in that range. Of course, there are ongoing operating costs from paying for electricity, rent, and server maintenance, and it scales from there, super linearly.

Let’s say you have $1 billion to spend. Assuming you wanted to put that all in one place, you might end up with a 12,000-rack data center, which is insane, right? It’s more than 100,000 servers. That doesn’t include any AI chips—no GPUs in that budget. That’s just buying servers and networking infrastructure. But if you’re spending that $1 billion on a data center specifically for AI purposes, for AI training, you could probably construct a data center with between 25,000 and 50,000 AI accelerators. An accelerator is, for example, an Nvidia GPU. So you basically are counting the number of accelerators first—50,000 accelerators—and then you get all the servers and networking infrastructure and buildings needed to house all of that equipment.

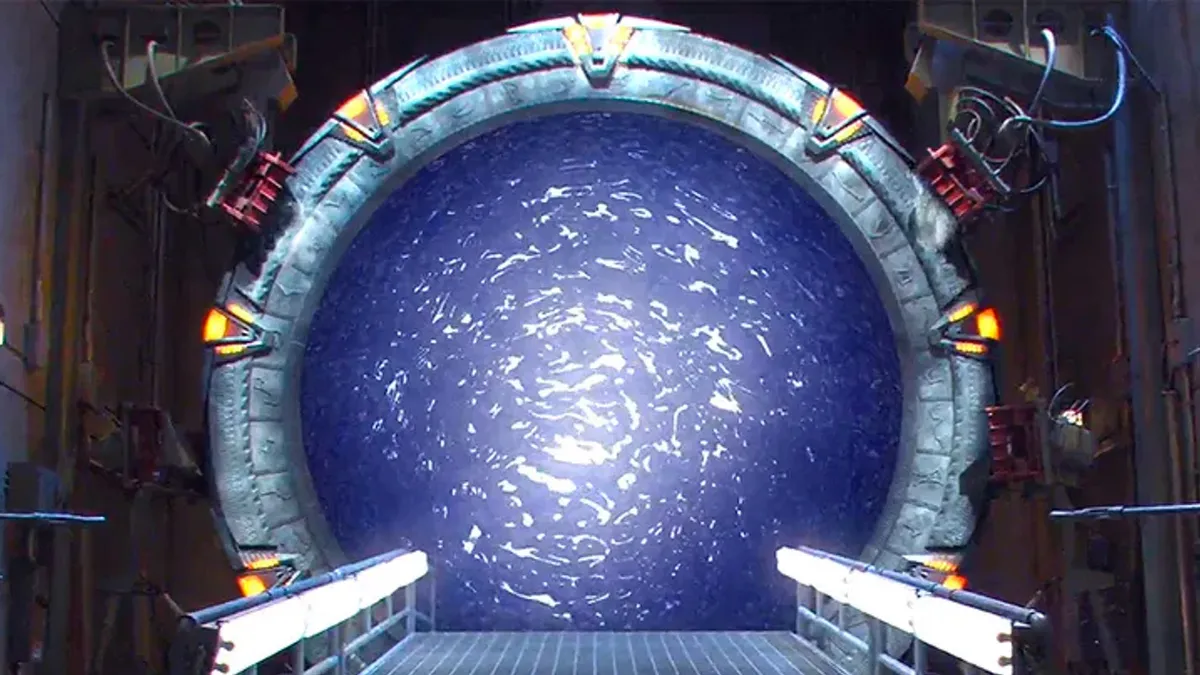

You might remember when, a couple of months ago, Sam Altman announced that he was trying to get $7 trillion to start creating new AI hardware. This was a very ambitious plan, and it’s probably not going forward. But you can see how the numbers get very large when you’re talking about AI infrastructure. The second version of OpenAI’s ask was for for $10 billion. That $7 trillion plan was instead of going to the Middle East for investment, just to rely on Microsoft. OpenAI instead asked asked Microsoft to build out Arrakis data center for $10 billion by 2026, which is supposed to be built in Wisconsin. Then a couple weeks later there was another headline news: a $100 billion next-generation AI data center is supposed to be created by Microsoft for OpenAI. This one is supposedly supposed to be built in Phoenix and be finished by 2028. Again, this would be an OpenAI and Microsoft collaboration, although Microsoft would be providing all the funds, and it’s contingent on OpenAI continuing to make significant advances. This project’s code name is Stargate, named after the science fiction TV show where you can step into a Stargate and emerge instantaneously in a different place in the galaxy or even, in the expansion Stargate Andromeda, in a different galaxy altogether. Probably named this because once we build it, we are creating AI on it that we don’t know what it will look like. So it’s like stepping through a Stargate—it’s our portal into the AI future. One of the engineers working on the project was complaining, “We can only put 100,000 GPUs in any given state without blowing the power grid.” Because OpenAI would want this system as fast as possible, they have to accelerate the timelines wherever possible and not spend a lot of time building up power infrastructure and so on.

Microsoft isn’t the only company making really big investments into AI infrastructure right now, though. For example, Amazon, which is currently the largest cloud provider in the world, has committed $148 billion to be put towards data centers over the next 15 years. These data centers are going to specifically service the AI boom. So this is a much longer-term plan, right? It’s a 15-year investment instead of just a 4-year investment. This shows a similar amount of commitment from Amazon to really provide the cloud computing that AI companies need. Then, of course, there’s Google, which is also investing a lot into its own AI models. Google has Google Cloud, which is a public cloud, but it’s only about the third in the world behind Microsoft’s Azure and Amazon’s AWS. However, Google has huge internal infrastructure. They had 135 data centers way back in 2021 and they have amazing software infrastructure that runs on top of those data centers. Their system for running arbitrary jobs from Google employees is called Borg. Because of Google’s investment in a particular type of AI hardware, they actually have a substantial lead on the competitors.

You might stop to ask, do we actually need that much compute? Are the number of AI models going to keep growing and the size of each individual model keep growing such that we need so much additional hardware investment? The answer is probably yes. The key to unlocking AI capabilities so far has always been to add more and more scale. At some point, you’re only limited by the amount of hardware compute you have and the amount of data that you have. There are techniques around the data shortage, such as synthetic data generation. But when it comes down to it, if you have access to more AI hardware, you’ll definitely find a use for it. While it’s true that more efficient training techniques for AI will probably be created eventually, no matter how efficient the technique, it will still benefit from additional scale.

Part 2: So You Want to Build a Data Center

Creating a data center is an enormously expensive and complex undertaking. They aren’t one-size-fits-all. You have to think about the problem you’re trying to solve and design something that works for it. For example, what are you going to be computing? What communication patterns will be needed? What ratios will you need between the different resources, such as networking and disk performance and CPU and GPU performance? Finally, how do you deal with resilience and redundancy? Because when you have a data center with thousands of computers, it’s actually fairly common for one of the computers or components to just fail, to stop working. The data center, like the internet as a whole, has to figure out how to reroute around the broken components and keep working.

Some of those design problems are pretty abstract, but let’s go through a few concrete problems that you’re going to have to solve as you build a data center.

Design Challenge 1: Power Consumption

First, you have to worry about power consumption. Running thousands of computers needs an extraordinary amount of power. For the Stargate data center specifically, they’re considering nuclear power as a potential source, and they even hired a nuclear expert to try to sketch out what that would look like. Many data centers are located next to hydroelectric dams or other sources of very cheap electricity. You also want a very reliable source of electricity because switching to backup generators is expensive. You might have seen this number elsewhere because people talk about it a lot, but data centers currently consume between 1 and 1.4% of the entire energy budget of the world. That’s between 240 and 340 terawatts of power per year. On the face of it, you would need more than 100 massive coal-fired power plants to actually produce that much electricity. So people talk a lot about the environmental impact of data centers, but the truth is companies investing in data centers are fairly wealthy. They prefer to use renewable energy sources whenever possible because it makes their image look better. Of that 240 to 340 terawatts of power, between 15 and 20% of it, or about 50 terawatts, is purchased from renewable energy sources by only four companies: Amazon, Microsoft, Meta, and Google. For example, Amazon, the biggest provider, was actually 85% renewable in 2021. Other companies, including Google, have pledged to become 100% renewable energy by some certain date in the future.

We’re also not talking about the companies purchasing carbon credits here, which is a common hack for a company to say, for example, “Our office is fully environmentally friendly and powered by renewable energy sources.” They actually just use power from coal-fired power plants and then supposedly buy the same amount of renewable energy somewhere else in the world. But the carbon offset market has dramatically collapsed. I think the value of those credits is less than 10% of what it was a few years ago. Basically, too many companies wanted to purchase these credits because it made them look good, but all that money wasn’t actually being used effectively. So that’s a whole other debacle. But basically, when it comes to data centers, this renewable energy is actually in the form of pre-purchased electricity from power grids. The company will say, for example, “I’ll pre-purchase this amount of energy from you every year for the next 20 years because I’ll need it to run my data center that’s located right there.” The environmental impact of power consumption by data centers is a little bit overrated. It’s great to highlight this issue and to put a spotlight on it to force these companies to continue purchasing renewable energy sources, but they’re doing a decent job of it so far. Having those really long-lasting contracts for energy purchase is great for renewable energy projects because they often have to amortize a really big upfront cost over decades. But a data center is such a huge investment that they know it will be around for decades, so they’re willing to commit to purchasing the power.

Design Challenge 2: Cooling

After power, the next big factor when designing a data center is cooling. The problem is that CPUs and servers run really hot. When you cram all the servers as close as possible into a rack, and then you cram all the racks as close as possible to each other, the entire thing gets very hot indeed. In fact, for most data centers, the power consumed for cooling is greater than the energy used to run the actual servers. So all data centers have to try to keep cool. Many are located in cooler climates, which makes your job easier, and a large portion also tries to leverage water cooling by taking cold water from lakes, rivers, or oceans and having a big data center-scale water cooler. Although Google actually has a different design point here—they let the air get to 80 or 95 degrees Fahrenheit (27 or 35 degrees Celsius) even in the cold aisles between the servers, which means the servers themselves are running hotter, probably more like 110 degrees Fahrenheit (43 degrees Celsius). Google has to be able to tolerate more equipment failing as a result because it’s running so hot. But they do this because historically they were using much cheaper machines that weren’t as high quality, so they weren’t going to last very long anyway. They can do it only because they’re very good at handling failures, even though they would have a much higher failure rate than other data centers.

Design Challenge 3: Networking

One computer on its own is not very useful. You have to hook up all the computers into a network. Often, because the servers have to work together to get jobs done, the networking inside a data center is way, way faster than networking in the greater internet. Standard Ethernet these days is 1 gigabit, and if you have fiber internet, you have a 1 gigabit connection up and down probably. So that’s considered very fast for consumer internet. You can also get 10 gigabit Ethernet, which, if you’re an enthusiast, you might have connecting all the systems in your house or a company or university might have it connecting their own computers. Beyond 10 gigabits, you get 40 gigabits, 100 gigabits, and even 400 gigabit network connectivity. The higher speeds are not using normal wires, which we call copper links. They’re actually using optical links; they’re using fiber optic cables. A fiber optic cable is basically a cable made out of glass with a hole down the middle, and you shoot lasers down the middle. It bounces off the sides and reaches the other end. You do need repeaters along the way to make sure to handle the few stray electrons that manage to escape the fiber optic cable, but this is incredibly high bandwidth. They actually use it to transmit information underneath the ocean through the transcontinental networking cables. That’s how someone in North America can access a website in Japan or Europe. The really cool thing about fiber optic cables is you can actually use different wavelengths of light, which don’t interfere with each other, to transmit information down the same fiber optic cable. Currently, for example, data center networking maxes out at 400 gigabit connections multiplexed over 96 channels. So basically, one fiber optic cable can get you 40 terabits of bandwidth. The specs on the cables that they lay underneath the ocean are not public, but they also have tens or hundreds of connections per fiber optic cable, and the cable as a whole is a huge bundle of those fiber optics.

In a data center, you have to first think about the intra-rack connections, the networking connections within one rack. You want those to be as fast as possible. Companies often use a technology called Infiniband and that’s what OpenAI wants to use for Stargate. If you have GPUs, then you often create a special GPU-to-GPU network that’s called NVLink if you’re using Nvidia GPUs. NVLink maxes out at 256 GPUs on one interconnected mesh, but Google’s TPU v4s can actually go up to 4,096 TPUs all connected together. Again, this is independent of the normal network that might be used to communicate between servers. Once you start creating the connections between racks—inter-rack connections—you try to use as fast of a cable as you possibly can, but pretty quickly you have to start using optical links instead of copper links, which are a lot more expensive. But you don’t have any option because of the amount of bandwidth required.

Design Challenge 4: Resilience and Redundancy

Actually, all of the aforementioned systems have to have a lot of redundancy built into them. You have to make sure there’s redundancy in power. There has to be more power available than you actually need, and if the primary power source goes down, you have to have fairly reliable backup power sources like backup generators or an entirely separate grid, etc. Cooling systems have to have a lot of different backups. Maybe it’s very hot, or there’s extreme weather going on because the last thing you want is to spend tons of money on a data center only to have all the equipment, all the CPUs throttled, running much slower because they’re overheating or having to replace them a lot more frequently. Networking as well is one of the components that tends to fail fairly frequently or require disruptive updates. So ideally, there’s enough redundancy in your backbone and also the individual connections between racks and within racks so that if individual links go down or aren’t working so well, you can route around the problem. This isn’t as easy as on the regular internet, which is a little more diverse, because data centers often have a very strict hierarchical structure to their network connectivity. This is the only way to keep the complexity under control and not have your network be ten times as large as it actually is. But it also makes it more sensitive to failures of individual links because they can really impact the available bandwidth for the whole system. So really, resilience and redundancy have to be considered at every step of the design process.

Actually, it’s good practice not to rely on only one data center. There could be natural disasters, for example, an earthquake or a flood, that could cause you to lose all the data stored on your servers or at least have the servers interrupted for a while while you bring it back up. This is one reason that most companies like to use the cloud to provide their infrastructure. They can’t afford to build three different data centers, but they can rent servers from three different Amazon data centers. People also use different regions for good latency. For example, if you have a server in Europe, then someone accessing it from Germany will have a much better experience than if they’re accessing the server across the Atlantic in North America. But even from a resiliency perspective, having a single region store all your data and all your servers is a really bad idea.

I should note that this matters less for the Stargate data center specifically because that one’s likely to be used for training AI systems. It wouldn’t be used for inference. So if it went down, then OpenAI researchers would experience delays, but they wouldn’t have customers unable to access their products. They definitely want to be able to get the biggest scale possible they can within one data center. That’s why they’re building a $100 billion data center instead of two data centers of roughly equal size, for example.

Part 3: The Hardware Secret Sauce

The big question is, what is doing the actual AI compute? We’ve heard Sam Altman say often enough that he needs more GPUs, so you might think that the answer is obvious—that GPUs are doing the compute. But that’s not necessarily the case. Regardless, you do need some special-purpose hardware and software to support it within an AI data center. There are only two major players here: Nvidia and Google. Of course, other companies are trying to get there. AMD makes their own GPUs, for example, and Microsoft is also trying to create AI-specific chips. But there are huge hurdles for them to overcome. So right now, only two players. Let’s talk about the hardware stacks.

Nvidia

Nvidia creates the designs for their own GPUs. They have a monopoly on the GPU market as far as AI is concerned because Nvidia created and owns the language CUDA, which is what’s used to program their GPUs. Simply because Nvidia GPUs were the most powerful in the past, all of the AI infrastructure has been built on top of CUDA. Although AMD has some very good GPUs, they’re not really allowed to copy CUDA because that’s owned by Nvidia. So they have to recreate a lot of this infrastructure that already exists for Nvidia. Anyway, Nvidia charges very high prices for their data center GPUs, which are different from the GPUs that you would buy for a gaming computer. Their data center GPUs cost about $30,000 each. These are powerful GPUs, but Nvidia’s gross profit margin is 76%. Every company wishes it could have 76% profit margins.

As a consumer, you can spend a fraction of the $30,000 by getting the consumer-grade GPUs instead, which is why, as an individual or a research group, it’s been very fashionable to build your own ML training cluster. You can just buy the consumer-grade GPUs if you’re small enough and you don’t have to worry about the data center licensing. But if you’re actually building a data center of a certain scale, then Nvidia requires you to buy these more expensive GPUs because there just isn’t any alternative—not a commercially available one anyway.

Google has hardware components called TPUs (Tensor Processing Units). Google first started designing them in 2013, and the first TPUs came out in 2016. They’re now on version five of the TPUs. These are special-purpose hardware intended exclusively for the calculations needed for machine learning. This is mostly for machine learning training, although there is an inference-specific TPU as well. Every component of the TPU stack is maintained by Google. They create the hardware, the compiler, and the software. If you’ve heard of TensorFlow, the software library, that’s generally the interface through which normal people access TPUs. TPUs are special-purpose hardware. From a microarchitectural perspective, they’re very interesting. There’s no dedicated instruction cache, probably so that as much cache as possible can be used for matrix data if the designer wants. The caches for vectors are not automatic—you have to program them. Caches on almost anything else, from CPUs to GPUs, are managed by the hardware because it’s a huge nightmare to do it from software. Google’s control over the compiler technology used for TPUs allows them to push that complexity into software. TPUs also have a network designed especially for them, so it’s not just the computations; it’s also the communications between nodes. The TPU network is shaped like a big 3D torus, so there are always multiple paths to reach your destination. It’s a more complicated system than what Nvidia uses, which is basically just every Nvidia card connected to every other card. But it results in better scaling and probably better resilience as well. Google has a lot more experience than Nvidia at designing really big data center systems with all the components that implies, including networking. So they have a real advantage in these TPUs. But Google also has no interest in offering TPUs to the world for sale because Google can instead put the TPUs into their data center, put it on Google Cloud, and allow companies to actually pay them for all the compute and all the networking and to make sure that the TPUs run properly. Most companies don’t want to buy their own TPUs and run their own data centers anyway—they would much prefer to just go on the cloud. So it’s a win-win situation, really.

Software Stacks

Enough about the hardware stack; let’s switch focus for a minute to the software stack. Nvidia controls the programming language CUDA, which is used to control their GPUs, and that all of AI stuff depends on CUDA. That’s a big software moat for Nvidia. A little higher up the stack, you have PyTorch, which is the Python library that virtually all machine learning researchers and quite a few industry practitioners use. It was originally created by then Facebook, but it’s now open-sourced. For Stargate, OpenAI will almost certainly go standard here and use PyTorch because they hire a lot of researchers who are already familiar with PyTorch. There’s an alternative to PyTorch, though, and that is TensorFlow. That’s the one created by Google, which is C++-oriented, has better performance, and thinks more about the system. It’s probably better for production but a little too annoying for researchers. So it seems to be used primarily by some industry practitioners and, of course, by anyone working at Google.

Lets take a deep dive into one of the component of these two libraries which is “computational graph representation”. Basically, a user will say something like, “The matrix A equals the matrix B plus the matrix C,” or, “The vector x times the matrix M,” or something like that. The computational graph representation is something that both of these libraries create that represents the arithmetic tree of the operations you’re trying to do. So there’ll be a node for a plus, and the two children will be B and C. Or there’ll be a node for multiplication, and there’ll be X and M underneath it—something like that.

PyTorch actually uses Python reflection to do this. Because Python is an interpreted language, you can actually look at the structure of the code from the code itself. It’s like the program gets to read its own source code, and that’s how you can turn “A plus B” into some data structure that represents “A plus B,” instead of it just being a single line of Python code that you can just run once. TensorFlow does something similar by doing operator overloading. But once you have this tree that represents the mathematical operations you’re trying to do, you have to figure out how to transform that so it can run on the actual GPU/TPU hardware.

Google does this with something called the XLA (Accelerated Linear Algebra) compiler. It does support PyTorch, but that seems to be a little less common. It’s used all the time in TensorFlow. It takes this mathematical graph and has an intermediate representation called HLO (High-Level Optimizer) that can represent that. Then it can do some optimizations at that graph level, for example by combining operators into one composite operator if it’s something that the hardware supports, or by noticing subgraphs that are actually the same thing and computing it only once. Then XLA actually converts this intermediate representation into LLVM (Low-Level Virtual Machine) intermediate representation. LLVM is actually just compiler technology. LLVM has been used to create industry-standard C and C++ compilers along with many other languages, and LLVM has one of the best-in-class optimization mechanisms that exists in the world. So they run LLVM optimization on its intermediate representation to actually go and generate the final code that will run on the TPUs. That’s how they can handle the complexity of having these scratchpad programmable caches, for example. That’s something well within the capabilities of LLVM. LLVM is also used in the JavaScript interpreter of many web browsers, including Google Chrome. So the same code that runs when you load a web page is actually very similar to the code that runs when Google is trying to compile a very complicated machine learning problem down to run on their TPUs.

Will Stargate Use Their Own Chips and Network?

Getting back to the point at hand, how does this $100 billion investment fit in? That’s certainly enough money for Stargate to have special-purpose hardware created for it. Apparently, they actually haven’t decided yet whether they’ll purchase chips from Nvidia or potentially use some of Microsoft’s own in-house chips that they’re designing. They will certainly need a brand new networking design and configuration because there is nothing public that can be built at this scale. But they probably don’t have time to create new networking infrastructure and protocols from scratch; Google started theirs five years ago. One eye popping decision is that they were going to locate Stargate in Arizona. It’s very hot there, and there isn’t enough water around for cooling. Yes, Microsoft does have an Azure data center there, but really there must be a better option. And of course, power is going to be a really big problem. Like the earlier quote suggested, they’re having trouble putting more than 100,000 GPUs in one place. They might have to come up with their own power mechanism; they might have to build a nuclear power plant.

AI chips, whether it’s GPUs or TPUs or whatever, are very expensive and energy-intensive. A typical data center allocates 10 to 14 kilowatts per rack, but with current technology, that would rise to 40 to 60 kilowatts needed to power one rack of servers full of GPUs. Yes, new chips will be more power-efficient, etc., but power must be one of the top considerations that they have to solve before they can go forward with this project.

Implications of Building Stargate

As for the implications of building such a huge data center, well, it would unlock a lot of capabilities for OpenAI and/or Microsoft. Google will still have the edge, most likely, in terms of raw compute power because of all the TPUs that they have and will have. But having one singular data center with all of that hardware in one place means that massive training runs can be attempted and can execute in a reasonable period of time. So maybe the future of GPT-7 is bright.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we talked a lot about what goes into making an AI data center, from the capital expenditure—which is larger than traditional data centers—and the widespread interest in spending that money from Microsoft, Amazon, Google, and others. There are a lot of design problems for any data center, but especially for AI-specific ones because AI chips draw a lot more power per rack than you would allocate in a traditional data center. The designers have to consider how much power is used, how much cooling is provided, what type of networking infrastructure will be in place—because you can’t just connect every computer to every other computer with the fastest possible links; your entire data center will be filled with wires in that case. The designers also have to consider how to build in enough resilience and redundancy so that their data center can survive natural disasters, typical wear and tear on the equipment, and everything in between.

The actual AI-specific hardware that makes AI data centers interesting is provided by really only two major players right now: Nvidia and Google. Nvidia’s GPUs are really the only option in the marketplace that’s commercially available, and they maintain this advantage over other GPU manufacturers by controlling the CUDA technology, which allows them to get away with a gross profit margin of 76%. Meanwhile, Google has recreated all of the same infrastructure internally with their TPUs. To work with TPUs, it’s best if you know C++ and you can use TensorFlow. Other companies are considering creating their own AI-specific hardware as well, including Microsoft, but it takes quite a lot of time to build and prove that hardware along with creating all the software stack on top of it and all the networking around it and everything. So this $100 billion Stargate data center might have to use more off-the-shelf technologies because they’re trying to create it on a fairly tight timeline.

Dr. Waku

Dr. Waku

Comments

With an account on the Fediverse or Mastodon, you can respond to this post. Since Mastodon is decentralized, you can use your existing account hosted by another Mastodon server or compatible platform if you don't have an account on this one. Known non-private replies are displayed below.